Photo: Vinicius Taguchi

Using “green” infrastructure is a useful strategy for handling city stormwater, which may contain deicers and other contaminants from streets and sidewalks. Choosing the right method and ensuring it doesn’t cause unforeseen damage, however, is another matter.

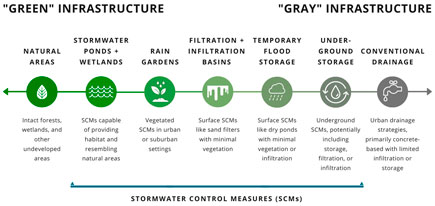

Green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) is a departure from more traditional, “gray” infrastructure in that it integrates natural functions of the environment. Used correctly, it can effectively utilize plants, microbes, and soil properties to trap or degrade pollutants, prevent soil erosion, and reduce stormwater volume. Since the early 2000s, GSI has steadily grown more prevalent as climate-change-altered precipitation patterns and increased land development force cities to rethink how they manage stormwater.

GSI must be used mindfully, however; there’s more than one method, each with specific strengths, weaknesses, maintenance requirements, and sometimes even social costs. A 2020 paper published in the journal Water outlines some of the more common challenges associated with GSI and offers a framework for how to handle them.

“Due to the growing interest in GSI,” the authors write, “it is easy to overlook potential trade-offs and unintended consequences that may accompany infrastructural attempts to address flooding and urban water quality issues.”

The specific GSI method being used has to fit the environment. Infiltration systems, for example, can filter and sequester large volumes of excess stormwater into the water table. However, the soil has to be the right composition, and certain pollutants—such as organics—are easier to filter out than others, such as nitrates or chloride.

Maintenance is another often overlooked aspect of GSI. Filtration systems are enhanced with media to retain dissolved contaminants and can “clean” stormwater runoff, but they require regular maintenance. Even strategies seen as low maintenance or “passive” require upkeep; the sediment that collects in stormwater ponds after rain events needs to be dredged on a regular basis so that the ponds don’t release their sequestered pollutants back into the environment.

“There’s so much about maintenance we don’t understand,” says Vinicius Taguchi, a Ph.D. candidate in civil engineering (advised by Professor John Gulliver) and the lead author of the paper. “If you’re not building it properly, if you’re not maintaining it properly, are you still doing some good?”

Image: Vinicius Taguchi

The final factor that the paper considers is the social impact of GSI. Installing “green” infrastructure, even something as simple as trees, can raise property values and rents—essentially a form of gentrification. Lower-income communities may also lack the funds to keep up their GSI, leading to defunct infrastructure that causes more problems than it solves.

The 2020 paper offers a framework for the GSI decision-making process, beginning with making and prioritizing goals: deciding what needs to be fixed and ensuring that one solution will not cause greater problems elsewhere.

The final decision should take into account the varying strengths, weaknesses, and maintenance needs of the strategy used, the researchers advise, and once the GSI is installed, it should be monitored and re-evaluated regularly to ensure it continues to be effective.

“We definitely want this to be a useful tool,” Taguchi says. “Hopefully, people who read through this paper will have an idea of how to think through this specific situation, or at least know that they need to have some questions for researchers with more experience.”