Safety and Urban Air Mobility

Demoz Gebre-Egziabher, Professor, Aerospace Engineering & Mechanics

Area of Expertise: Vehicle Systems

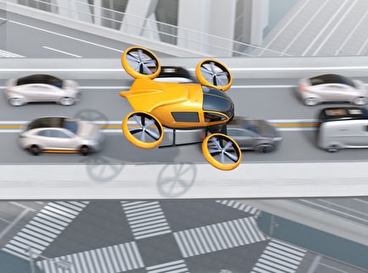

Autonomous aircraft and drones that can move people and goods in new ways are coming to our cities. Often referred to as Urban Air Mobility (UAM), these new transportation concepts are the flying equivalent of the autonomous car—and they raise just as many important questions about safety, use, and operations.

UAM technologies are envisioned for various applications in the future urban transportation system, including as package delivery vehicles, infrastructure inspection and environmental monitoring platforms, aerial ambulances, and on-demand public transportation systems (aerial analogs to today's Uber or Lyft). However, their promised future utility is tempered by the many daunting technical challenges that must be solved before they become a reality. Many of these technical challenges are the topics of intense current research at universities, government agencies (e.g., NASA, FAA, USAF), and private firms (e.g., Archer, Wisk, Pyka). Many equally challenging regulatory and policy questions must also be addressed before UAM becomes practical reality. In many ways, technical advances are being held back by the absence of a clearly articulated public policy associated with these transportation systems. To prepare our communities and systems for the wider use of UAM, we must also put into place a successful regulatory system. A case in point is the issue of safety, and safety certification, of UAM systems.

With respect to safety, local communities and agencies are stakeholders that must have a say and provide clear guidance to those developing technologies for UAM. The time for defining requirements for UAM safety is now, at the same moment when its enabling technologies are being developed.

To understand this challenge, consider the way in which conventional aerial systems are certified today. Traditionally, certifying that a new aircraft design is safe for use has been the responsibility of the FAA. Certifying a new aircraft design requires, in part, that manufacturers demonstrate that the risk of harm to passengers, the public, and property resulting from the use of their products is very remote. In more concrete terms, proving safety requires showing that the risk of harm is at least less than one in a million per hour of operation. This explicit requirement enables engineers and technologists to design and develop safe aircraft systems, operational procedures, and training standards for operators. Currently, such standards are uniform for a given class of aircraft (e.g., aircraft used in scheduled passenger service), and all are set at the federal level by the FAA.

No such system of regulation exists for UAM. There is a consensus that the current “one-size-fits-all” approach will be untenable for UAM because of the sheer diversity of the planned applications of these vehicles. For example, it is not reasonable to expect the same level of safety and reliability for a UAM used to carry produce from a rural farm in Western Minnesota to a warehouse on the outskirts of the Twin Cities metro area as for one ferrying passengers. Similarly, it does not make technical or economic sense to expect that the design and operation certification of a UAM used to inspect transportation infrastructure in the harsh winter environments of northern Minnesota would be the same as one used for a similar mission in the desert climate of the Southwest. This is why the UAM community acknowledges that setting design and operation standards will require some level of local and state involvement to account for unique localized contexts. It will also need local communities making decisions about the kind of UAM operations they are willing to accept or tolerate. This is not to say that the FAA does not or should not have a role—rather, what is needed is a coordinated effort by the FAA and local authorities.

UAM is a technology with the potential to revolutionize future transportation. With respect to safety, local communities and agencies are stakeholders that must have a say and provide clear guidance to those developing technologies for UAM. The time for defining requirements for UAM safety is now, at the same moment when its enabling technologies are being developed. This will ensure that technologies to support UAM development will be efficient. More importantly, however, it will ensure that UAM is a technology that is safe for the various stakeholders who will use use and live with this transportation technology in the future.