Highway projects in the U.S. have a long-standing history of dividing thriving minority communities to make way for vehicle travel. In recent years, there has been renewed interest, political willpower, and funding to address historical wrongs and repair divided communities. However, these efforts need to be directed carefully—with equitable planning and community engagement—to avoid repeating old mistakes.

In a MnDOT-funded project, researchers Frank Douma and Maya Sheikh from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs studied one approach: developing the rights-of-way and airspace near state highways. They found that infrastructure such as “caps” or land bridges over highways could support both community health and economic growth.

Douma and Sheikh conducted eight case studies in communities across the nation to examine how public and private resources were used—to greater and lesser effect—to improve the land surrounding highways. They compiled best practices and presented their findings in an online workshop and symposium on August 15.

Speakers provided their on-the-ground perspectives on case studies from Atlanta, Milwaukee, Washington, DC, and the Twin Cities, while other presenters gave a broader perspective on national trends.

Cities have traditionally been built with the intention of delivering vehicle traffic directly into the heart of the city as fast as possible, said Peter Park, associate professor adjunct at the University of Colorado and a former city planner for Milwaukee and Denver. However, highways tend to make city blocks bigger, limit access, widen streets, increase redundant travel, and overall reduce the performance and capacity of a transportation system. With infrastructure aging out, he said, there is now an opportunity to rebuild with people—not cars—in mind.

Engaging the community’s needs

The first of Douma and Sheikh’s best practices is recognizing that infrastructure alone cannot be relied upon to fix community wounds. “A lot of these cases come from situations where infrastructure caused the issues that we see,” Douma said.

Engaging and addressing the interests of local and surrounding communities is important for mitigating unintentional damage, Sheikh added, as is having a transparent governance process.

Paul Angelone, senior director of the Curtis Infrastructure Initiative, presented the idea of “caps” and “stitches”—which are ways of partially reconnecting land on either side of a highway. A cap is basically a wide bridge that can be enhanced with green space, foot travel access, and other features, and a stitch is a narrower version of a cap.

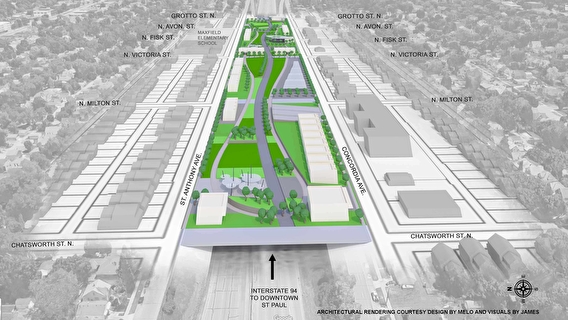

Keith Baker, executive director of ReConnect Rondo, demonstrated a positive example of how a cap could be put to practical use. Rondo is a St. Paul African-American community that was divided by I-94 in the 1950s and1960s. A prosperity study done by ReConnect Rondo found that around 700 homes were lost when the freeway went in, and an intergenerational wealth gap of -$157 million in unrealized home equity value had developed as of 2018.

ReConnect Rondo is looking to build a cap over I-94 that would reconnect the divided halves of the community. The project, which would cost around $459 million, could potentially free up 21 acres of land and add around 1,800 new jobs to the area.

Baker said it will be important to ensure that community input be taken into account as the project progresses. “We see the early principle of community ownership as critical for driving transportation investment,” Baker said. “Again, we’re talking about righting past wrongs.”

Maintaining funding

Another best practice—from a more administrative perspective—that Douma and Sheikh drew attention to is that highway improvement projects need to maintain the “transportation purpose” of the affected infrastructure.

Legally, said David Nguyen from the Wisconsin DOT, freeways built using federal money must serve a “public highway purpose,” and if the removal or alteration of a freeway undercuts that purpose, the money has to be given back. However, clauses to this rule can be leveraged if the changes are in the public interest, do not impair the highway itself, or will not interfere with the flow of traffic.

In Milwaukee, for example, the Park East Freeway was removed in 2002. The Federal Highway Administration ultimately waived the public highway purpose requirement because the removal was proven to benefit public transportation needs. Congestion was reduced, and connectivity between downtown and the near north side of Milwaukee was improved, Nguyen said.

A final example of innovative funding is the Capitol Crossing highway cap in Washington, DC. Angelone highlighted the unusual level of private funding that allowed the cap to get beyond the planning stages and embrace environmentally friendly planning and building practices. The project is also a notable example of airspace use agreements.

If a freeway cannot be removed outright, Douma added, there are resources such as right-of-way agreements, utility accommodations, and airspace lease agreements that could be creatively leveraged to improve the land around a freeway. The projects around the Milwaukee I-794 are an example. “You can do this while keeping the core use of the highway intact,” he said.

Returning value to the community

Another best practice is ensuring that the funds generated by improvement projects return to the affected communities.

Gentrification, Park said, is a significant issue that needs to be considered, as “improvement” projects will often increase property values in an area and drive out locals who can’t afford rising housing costs.

Sweet Auburn, Georgia, is a 170-year-old African-American community east of downtown Atlanta that was divided in the 1940s and 1950s by the I-75/85 downtown connector freeway.

LeJuano Varnell, executive director of Sweet Auburn Works, says that fixing the damage caused by the freeway—depressed property values, increased CO2 emissions, loss of historic and neighborhood fabric—will need to focus on putting control of the land back into the hands of the people living there. “The empathy that comes from a real estate development has everything to do with the owner,” Varnell said.

In Washington, DC, the 11th Street Bridge Park project is attempting to mitigate gentrification through careful use of community engagement. The aim of the project is to convert a defunct freeway bridge over the Anacostia River into a pedestrian footbridge. From the very beginning, said Scott Kratz, senior vice president of Building Bridges Across the River, the local minority communities were involved in the planning process.

Two years were spent engaging with the community even before engineers and architects were approached, and the 11th Street Bridge Park’s Equitable Development Plan was created to lay out and address potential problems, Kratz said. A homebuyer’s plan and a land trust were created to generate affordable housing, and a construction training program was created to ensure that the $90 million project costs were returned to local workers as much as possible.

Overall, Douma concluded, community engagement is one of the most important aspects of remedying the harms of past infrastructure projects. “If one starts by trying to sell a vision rather than by understanding the community’s vision, you will likely run into some problems.”

A recording of the symposium and a summary proceedings will be available on the MnDOT project web page.

Writer: Sophie Koch